8 takeaways from CES ‘26

In this third year of AI-powered everything, CES once again raised a familiar question for us: Just because we can build something, should we?

At IDEO, we approach CES the same way we approach any design challenge—with a human-centered lens. We’re interested in how new technologies fit into real lives, not just how impressive they look on a show floor. CES is valuable precisely because it reveals where ambition meets assumption: what companies think people want, what they think people will tolerate and pay for, and what they think people are ready to trust.

This year, alongside our partners at Autodesk, we spoke about preserving the human touch in AI-enabled design: helping teams move faster without losing sight of the people they’re designing for. That tension echoed throughout the show, from autonomous vehicles to health tech to gaming.

Here are the themes and ideas that stayed with us, and the questions they raised about how technology can better serve real human needs.

1. Are we designing better products or better outcomes?

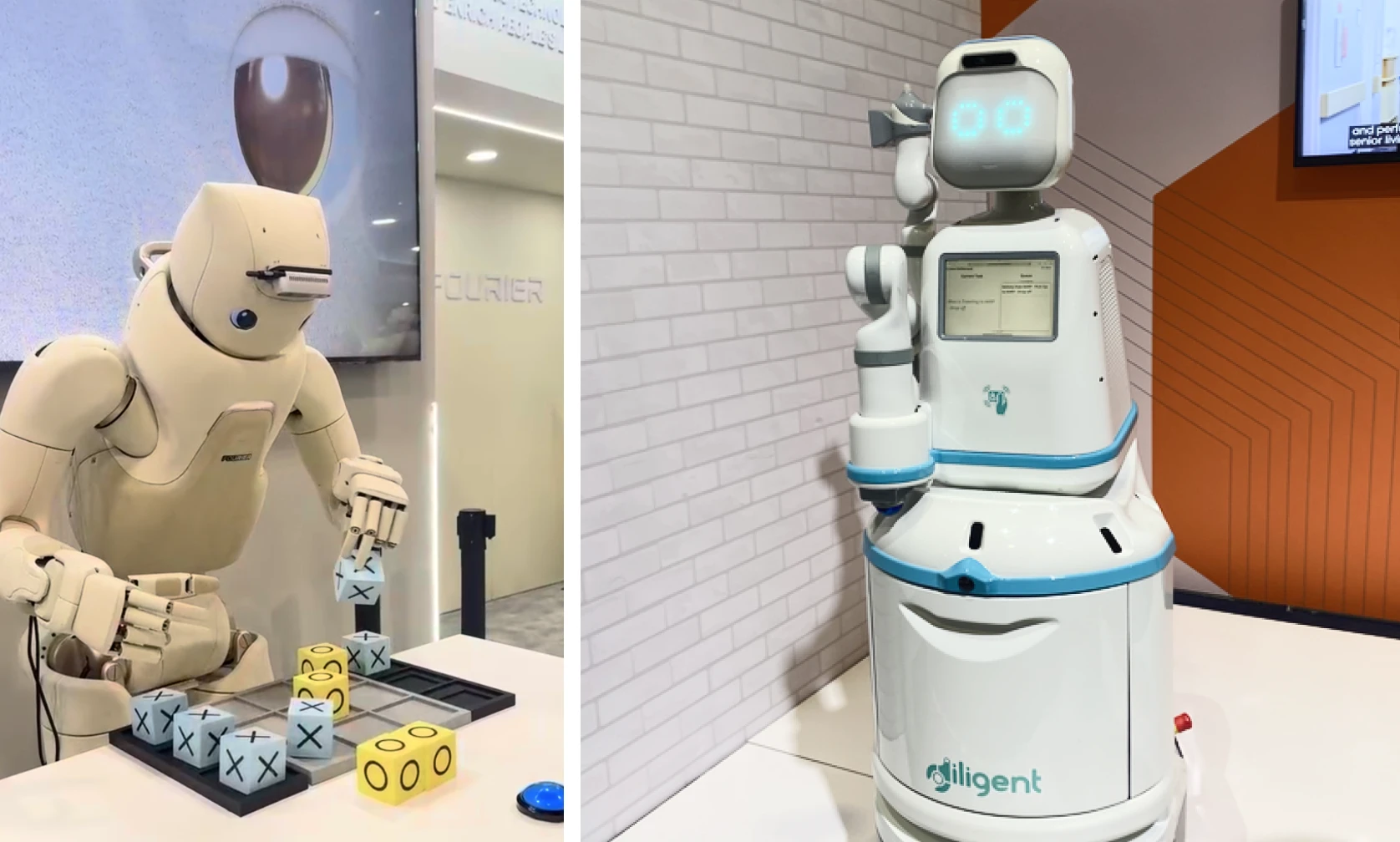

Everywhere we went, companies were going all in on humanoid robots taking on mundane human tasks: loading dishwashers, tidying kitchens, picking up socks. But a conversation with The Verge publisher Helen Havlak prompted us to wonder whether these machines were solving the right problem in the first place.

Training a robot to load a dishwasher in a private home is an astonishingly complex challenge. It requires object recognition, dexterity, spatial reasoning, and an understanding of a customized environment designed entirely for human hands. But if you step back to ask the fundamental question—what is the most effective way to clean dishes?—the answer is probably a box that washes them.

We don’t need a humanoid assistant to load and unload dishes more efficiently. We need a system that reliably turns dirty things into clean ones—which, for the most part, we already have. The more useful design challenge may be less about building ever-smarter robots and more about rethinking the environments in which those tools operate. What if smart appliances adjusted their capacity, energy use, and footprint based on how many people were in the home that week—or even that day? Or what if companies focused less on replicating human motion and more on solving the parts of domestic labor that still lack good machine-based solutions, like tackling the mental load of household management? These questions shift the focus from mimicking human behavior to redesigning systems around real needs, constraints, and rhythms of everyday life.

2. The nostalgic appeal of ditching screens

In between the glut of AI demos and autonomous everything, we saw something unexpected: a CD player blasting Britney Spears. As much as we enjoyed the throwback moment, it captured something deeper than nostalgia. In a world defined by speed and abstraction, there’s a growing desire for technology that feels tangible and controllable. From pinball machines to screen-free experiences for kids (like Tonies), these products aren’t trying to do more on our behalf; they’re designed to restore our agency. You know what they do, how they work, and when to turn them off.

We’re seeing this play out culturally, too. Parents are buying landlines to give younger children agency and an option to connect with their friends and grandparents without increasing their screen time or exposing them to online risks. In our own research with a slightly older cohort—Gen Z—we found there is a clear limit to how much they want technology to interfere in their lives, particularly when it comes to developing their own creativity or building relationships. Choosing simpler tools can be a way of reclaiming agency. Sometimes consumers really want less, not more.

3. The body as a platform—and who gets to own it

“Longevity” was definitely a buzzword this year. The conversation is shifting from optimizing performance (the domain of elite athletes and body hackers) to how technology supports living longer, healthier, and more independent lives. We were encouraged to see this reflected not only in products for aging populations, with the continued presence of AARP and age tech, but also in growing attention to women’s health, fertility, and everyday wellbeing (areas we noted were missing or underrepresented in 2025).

What stood out wasn’t that so many products were collecting health data—it was how they were collecting it. At one end of the spectrum were products that relied on clearly defined wearables—such as Neurable or Plaud—which ask users to consciously opt in by strapping technology onto their bodies. On the other end were more ambient approaches, embedding sensors into everyday objects and places, from smart toilets (assessing biomarkers linked to hydration, infection, metabolic health, and digestive function) to doorways (tracking movement to infer activity, safety, or well-being). The benefits are convenience and invisibility, but such devices also raise questions about consent, agency, and trust. Does a guest who uses a toilet automatically consent to a urine test? Or having their movements monitored? Do aging parents, or teens who share your toilet?

And what about data storage? As more of our biological signals are captured, where does that information live—and who controls access to it? Alongside familiar cloud-based subscription models, we saw emerging alternatives that store personal health data locally at home. These approaches hint at a future in which people retain more autonomy over their most intimate information, rather than renting access to their bodies to a platform; but only if autonomy, consent, and control are treated as core design requirements, not tradeoffs made in the name of convenience.

4. The body as an interface

We were also heartened to see meaningful progress in accessibility: devices that translate on-screen text into dynamic Braille, glasses that support navigation for people with low vision, and exoskeletons designed not only for rehabilitation, but for recreation and everyday work. Together, these examples point to a broader shift: one where the body is increasingly treated as an interface. How exactly it will happen is still to be designed. Whether these systems empower people with greater agency and dignity will depend less on sensing technology itself and more on the choices designers make about desirability, consent, ownership, and control. We’d love to see these technology systems evolve to empower people to actively shape and adapt their own interfaces themselves, rather than being locked into assumptions companies make when they design. If past regulatory changes are any indication (such as the FDA’s move to establish a new over-the-counter hearing aid category), reducing friction and gatekeeping in these domains can lead to more inclusive, creative, and beneficial product innovation.

5. Joy, play, and delight are the end goals

In a year dominated by efficiency, optimization, and automation, the technologies that stood out were the ones that made us smile. As leaders in IDEO’s Play Lab, this wasn’t surprising—but it was still reassuring. As Steven Johnson explores in the book Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World, many of our most transformative technologies arrive through entertainment rather than technology alone. Play creates permission to explore and challenge existing ways of thinking.

This year, the floor featured fewer technologies that simply automate the parts of life we tolerate, and more tools that help people live more fully and even celebrate the wonder of being human. From the Sweekar pocket pet (a Tamagotchi-like companion device that uses AI to grow with you) to LEGO’s experiments with smart bricks, we were impressed by inviting products that lowered the barrier to entry by making curiosity feel safe and fun.

We saw the same impulse in the recreation and mobility space: AFEELA cars greeted passengers with emojis; Zoox’s autonomous vehicles offered starry ceilings; and Garmin shared tools that help people fish, kayak, or explore more confidently. These moments of delight carry value—they build trust, emotional resonance, and attachment, qualities that matter just as much as performance when companies are introducing unfamiliar technology into everyday life.

If last year’s CES reminded us that kids aren’t impressed by AI alone, this year reinforced a related truth: joy is often the mechanism that makes new technology feel usable, trustworthy, and worth inviting into everyday life.

6. The infrastructure advantage

One of the clearest signals from the floor at CES: Novelty alone is not enough. Regardless of how cool or advanced your product is, it’s hard to sustain a business on product alone. In an increasingly crowded landscape, the companies best positioned for sustained growth are shipping impressive products AND building the infrastructure to support them. That includes faster iteration cycles, deeper integration across components, and ecosystems that support repair, reuse, and evolution over time.

The contrast between iRobot and Dreame made this especially clear. iRobot helped make our Jetsons-era dreams of home robots feel real—so real that for many of us, the Roomba became shorthand for the category itself. But its products were largely designed to stand alone, with new product versions debuting on predictable release cycles. Dreame, by comparison, is thriving because it’s built on a portfolio—from robot vacuums to beauty tools to electric vehicles—where components, intelligence, and manufacturing capabilities are shared, reused, and continuously improved.

We saw this same infrastructure-first thinking at a larger scale, too. Concepts like Panasonic’s Leaf integrate power generation directly into the built environment, using perovskite solar cells embedded in windows so energy becomes a byproduct of spaces we already live and work in—rather than a separate system to manage.

7. Supporting existing behaviors

Rather than asking people to adopt entirely new behaviors when they buy a new product (such as remembering to charge yet another device or embrace a new daily ritual), some companies are designing products that quietly fit into existing habits. The Pebble Index 01, for example, is a small ring with a single button and microphone that acts as an external memory for your brain, almost like a modern dictaphone. Its battery lasts for years, sidestepping one of the most common frustrations of modern tech: the need to manage endless charging cycles. Headphones with built-in cameras follow a similar logic, adding new capability to something people already wear every day. The Dreame Halo, a robotic hair dryer that doubles as an architectural floor lamp, pushes this idea to an interesting place, imagining a future where technology integrates so seamlessly into daily life that even chores can feel relaxing and luxurious. These choices may seem incremental, but they reflect a deeper understanding of human-centered adoption: market success often comes from fitting into people’s lives as they are, not asking them to reorganize around a product.

8. What we hoped to see—and didn’t

Compared to CES 2025, the conversation about investment in sustainability and climate-forward innovation felt muted, squeezed by the urgency of the AI race and tightening capital markets.

We also found ourselves wishing for more attention to the content, brand, and systems that sit alongside hardware. As agentic commerce and AI-driven discovery reshape how products are discovered, it may become even harder for smaller upstarts—such as the many companies filling Eureka Hall—to stand out in a landscape trained on decades of legacy data and dominant brands. Designing a great product is only part of the challenge; investing in brand, narrative, and trust signals that help new ideas be recognized, remembered, and chosen may be just as critical.

(Special thanks to Tiange Wang and Zoey Zhu for their contributions to this story, and credit to the Consumer Technology Association (CTA)® for the header image.)

Words and art

Subscribe

.svg)

.webp)

.webp)