What Your Name Says About You

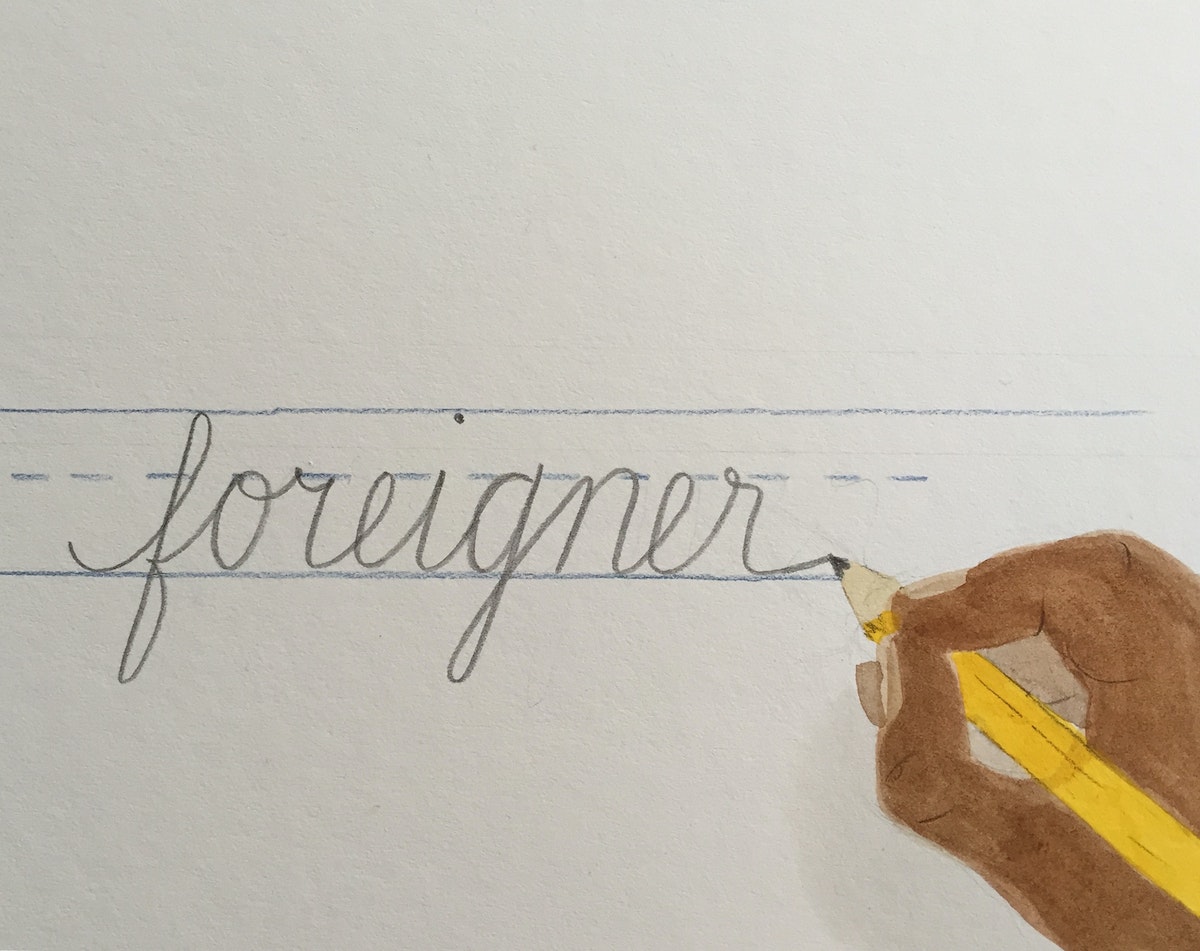

In the first week of kindergarten in rural Ohio, I learned to write my name. The teacher probably thought it would be an easy lesson. My classmates had names like Amy Lewis, Leslie Williams, Jennifer Green. I imagine her blithely scanning the attendance sheet, then getting to my name and thinking something along the lines of “We’re gonna need a bigger boat.” That was how I first learned I was different: eking out cursive letters long after the others had moved on.

People squint at "Adwoa" and tell me how creative my parents are. But my name is not that unusual in Ghana, where my parents are from. It just means that I’m a girl who was born on a Monday. My mother is also an Adwoa: We are legion. It was hard to explain that growing up, and even harder to fit in with my many cousins when I went back to Ghana for all too brief visits. I had the name, but not the language, culture, or history I’d need to belong.

I spent a lot of my school years apologizing for that name; it felt like an albatross around my neck. I used nicknames, and prefaced my response with, “it’s a long one!” whenever anyone asked me to spell it out. And then I got to high school.

Over the years I’d become keenly aware of the long pause that ensued on the first day of school, as the teacher taking attendance nervously approached the end of the Gs. So I was shocked to find that when she did pause, it wasn’t just on my name. Oluwakemi Adegoke. Shuchi Dwivedi. Chloe Jhangiani. Fungai Machirori.

For the first time in my life, I wasn’t the only one weird one. Who was this magical tribe? It turned out they were all, like me, first generation Americans. They got it. Here were my people.

My life was upended by the realization that there were more of us than I’d ever thought possible. We held America within us, but we also had one foot on other shores. And the water between all of our feet was alive with shared experience.

East Asian friends and I laughed ourselves sore about our parents’ hyperzealous focus on education. (Overheard in my household: “Unless you are at death’s doorstep, you are going to school today.”) At the end of the year, we shared knowing glances when perfect attendance awards were given out.

Indian friends and I lamented our low tolerance for spice; Filipino friends teased me about our mutually lengthy names. I am still in disagreement with Nigerians about whose jollof rice is better (Ghanaian, obviously). As an undergraduate, my experience in the U.S. left me uniquely prepared to be a stranger while studying abroad in Italy and Portugal—I already knew all about shapeshifting to accommodate people’s expectations.

It was an Iranian-American professor who gave me back my name, shaking aside the abbreviations and waking me up to the fact that it should never have been a source of shame. My undergraduate thesis was about Sex and the City, which always makes people laugh. But it had a deep meaning for me. I used the show as text to unpack the way we construct our identities in urban spaces. When you come from somewhere else, as most New Yorkers do, people can only know you by what you show them. In arriving, you can transform into whoever you’d like to be.

Art that speaks directly to the labor of rebuilding home—El Anatsui’s paintings, the music of Alsarah and the Nubatones—is especially good at conjuring up the longing and resilience of those new beginnings that require us to reconfigure our very selves: our ways of expression, and of being in the world. Moving between two worlds is perhaps the ultimate design act.

Everyone has felt that they were different at some point in their lives; all of us have taken steps into the unknown. If we’re lucky, we’ve found our people there. At a time when the planet holds 65 million displaced people—the highest number in history—seeking out the shifting stories of those who aren’t like us is more important than ever. We may realize, along the way, that we’re all each other’s people.

Illustrations by Lisa Hsia.

Words and art

Subscribe

.svg)