To Become a Better Designer, Make Time for Make Believe

Think back to your first kiss. Remember the place, the smells, the nerves, the lips. If you had to create a cocktail to tell the story of that experience, how would you do it? Would you make Jolly Rancher–infused vodka to conjure the candy-loving kid next door? Would a popcorn garnish nod to the movie you barely watched? Answering these questions is how the designers of IDEO New York spent a Valentine’s Day afternoon.

Every other week, I host a creative playdate for our studio called MakeBelieveTime (MBT). We always come up with something different. Maybe we’ll combine magnets and mirrors to invent our own games. Maybe we’ll use a needle and thread to learn the basics of computer coding, or fold our hopes and fears into paper airplanes. MBT has become one of the tentpoles in our community’s calendar—a ritual that brings our bodies out of project spaces and our minds out of design mode. It’s playtime for adults.

The value of these exercises has become clear to us, but when visitors happen to be around for MBT, all the natural questions bubble up. Sounds fun, but you do this during work hours? (Yes.) Are these exercises used with clients later? (Sometimes, but not always.) How does this apply to paid project work? (It doesn’t.) So what’s the point?

That is the point. MakeBelieveTime is actually most valuable when it does not directly relate to project work in a typical, measurable way. It’s play for the sake of play, and that’s okay—in fact, it’s essential. Here’s why.

It’s about process, not product

I once had an art teacher who would sketch all over my work to show me different techniques. At first, I was frustrated because my brilliant piece was being scribbled on. But then I recognized his assumption—that an artist will do it again and again and again. That learning a new technique meant focusing on the hand, not the paper.

In our design work, we rely on our own experiences and intuition, so it’s essential that we become fluent in exploring our memories and feelings. MakeBelieveTime gives us a chance to practice that with new and unfamiliar tools. That’s why, whether it’s colored sand or temporary tattoos, the real materials of MakeBelieveTime are our personal joys, hopes, and fears.

It preps the mind for design

When I was a kid, my grandfather told me about Louis Pasteur’s belief that “Chance favors the prepared mind.” Show up and do the work, Grampa explained, so that when the magic happens you’ll be sharp enough to recognize it. Making space for “sensorial, analog, hands-on radness”—that’s how one colleague described MakeBelieveTime—gives designers a much needed mental reset.

Plus, MBT actually has made an impact on client work. A handful of insights and concepts that originally came out of MakeBelieveTime actually made it into an experience we designed for a major NYC landmark.

But that’s not really the point. It’s about helping our designers spread their nets as wide as possible, and to lighten things up with a moment of pure, playful joy, so that when inspiration comes they’re ready to grab it.

It broadcasts both values and value

Most designers will sing the praises of play. It opens you up and makes you braver, more optimistic, and more creative. We pepper client meetings with pipe-cleaner sculptures or a little improv to get the blood and imagination flowing. We put a lot of thought and energy into those activities, thinking about our clients’ needs and the best way to get them comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Most designers will also admit that when deadlines loom, proposals beckon, or clients push back, play is not always top-of-mind. That’s a problem. An organization’s beliefs come through in their actions. To show that play is worth the time, you have to make time for it.

How to build your own MakeBelieveTime

We want MBT to be much more than a free-for-all with glue sticks and googly eyes, so we use three key design principles to guide the activities:

- Make the familiar unfamiliar. To think about senses we take for granted, we infused finger paints with essential oils and asked everyone to visually illustrate the experience of smelling that scent.

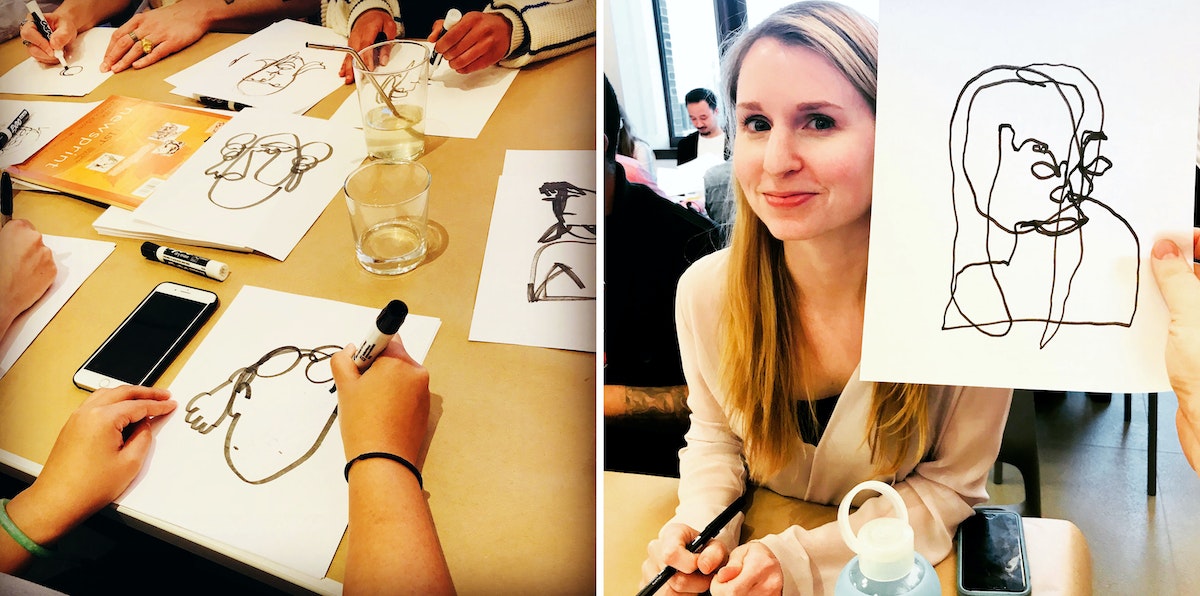

- Explore safe danger. Blind contour drawing is a great example. We all sit and draw the person across from us—without lifting the pen or looking down at the drawing. It’s always a mess, which guarantees a joyful, public fail, but also allows us to look deeply at each other and practice seeing and being seen.

- Dig deep. We used Halloween as a prompt to create a mask that evokes a moment we were horrified by our own behavior. This allowed us to acknowledge the full spectrum of our feelings, exorcise that shadow, and leave it to the past.

The first, despairing thought that hit one of my colleagues when he first saw MBT in action was, “IDEO’s gone soft.” And, quite frankly, that's not an unfair concern when you see a room full of world-class designers finger painting.

But MBT serves as an opportunity to nourish a perspective rather than achieve an objective. It’s less about the scented fingerpaints, and more about exploring new ways of understanding and sharing an experience. It’s also about laughing together. It’s about exposing our soft side so that we can trust each other more when we take those lessons back to our project spaces and have a hunch about trying something untested but exciting.

That’s why we believe that designing a cocktail that tells the story of your first kiss doesn’t cost you your edge. It’s how you keep it.

Words and art

Subscribe

.svg)