The Human-Centered Heart of California Design

If my heart were a painting, it would be on permanent loan to California. I love its shaggy optimists who turn drained swimming pools into skate parks. Its fog and fearless politics. Its pioneers and garage inventors and beat poets who came in search of a Golden State. I'm a big believer in the design that was born here, too, which is on display at the SFMOMA’s "Designed in California" exhibit through May 27, 2018.

Smartly curated by Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, the show features objects dating back to the late 1950s, from the Eames Office to the first iPod to a home CRISPR kit.

I've now seen the show twice. Here's what’s stuck with me:

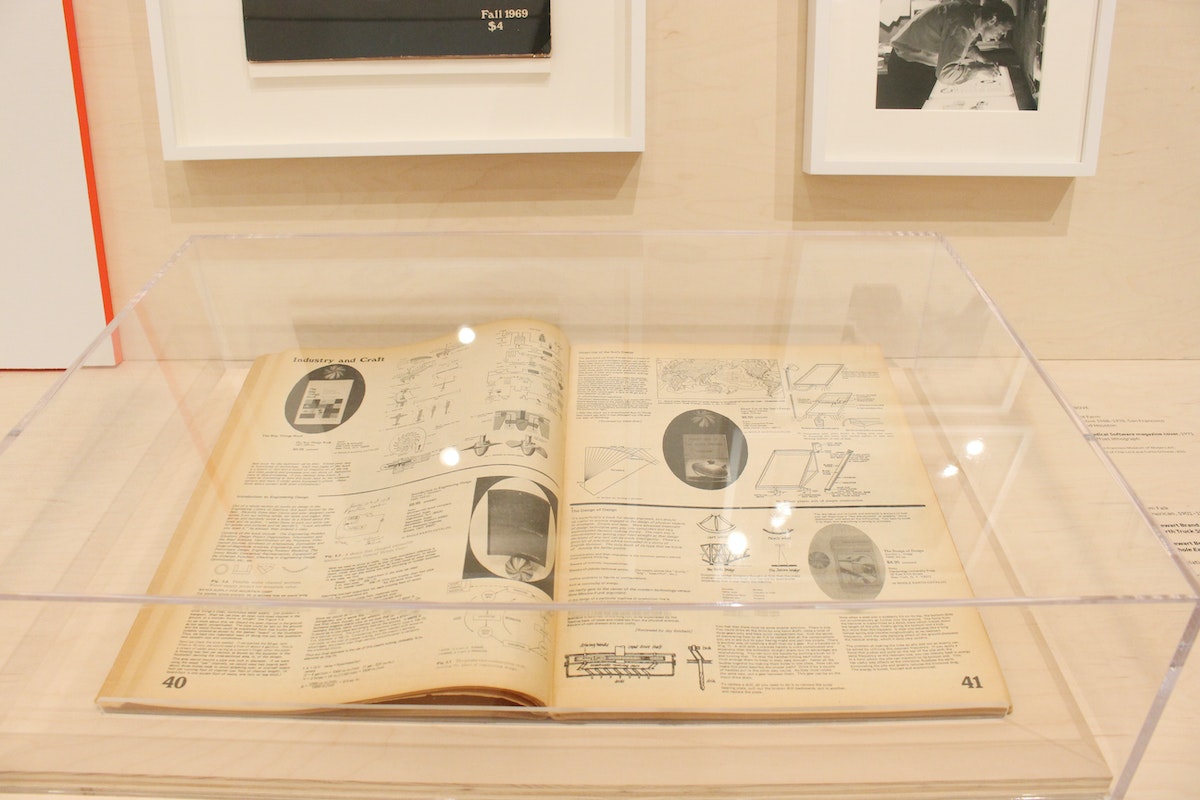

So much of what comes out of Silicon Valley today has its roots in the DIY utopianism of the Whole Earth Catalog. Founded in the late 60s by Stewart Brand and a bunch of Stanford longhairs, the Catalog promised “access to tools" that would equip us to break free from our hidebound culture.

The title was inspired by Brand’s 1966 campaign to have NASA release a satellite photo of the Earth as seen from space—the first image we’d see of the "whole Earth." That picture, he believed, would unite humans in our belief in a shared destiny and encourage more peaceful, ecological, and holistic thinking.

When I was in my 20s, the Whole Earth Catalog spurred me to start my own DIY design magazine, ReadyMade, in the back of a used furniture warehouse in Berkeley. Whole Earth made designing a life on one's own terms seem within reach.

That spirit shines through in another standout of the exhibit: the recreated office of Charles and Ray Eames, down to the posters on the wall, the kilim rug, and a looping projection of their film for the World’s Fair (a serenade to industry and systems design). Everything they laid their mid-century paws on exudes a kind of singing-nun joy. Two things I love most about them: their philosophy that “Eventually everything connects—people, ideas, objects,” and that they employed the people they were designing for—Los Angeles locals, war veterans, and housewives.

There’s also the agitprop hijinks of Ant Farm; the stained leather scrappiness and propaganda of Marin’s craft guilds; and Heath Ceramics—the tableware preferred by my avocado toast.

And for us outdoorsy types, the centerpiece of the exhibit is a Bucky Fuller-inspired North Face tent, pitched alongside radically new 1970s climbing equipment made by Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia.

I had a feeling the iconic "one laptop per child" by fuseproject would be on hand (check!), and was excited to see my friend Eric's (of Stamen Design) dazzling data visualizations.

Having done a tour of duty at WIRED in its third year of publication (1995), it was great to see their eye-popping cyberpunk spreads on display, and I'm always happy to learn of companies like D-Rev that care enough about social impact to design an $80 high-performance knee (80 percent of the world's amputees have no access to modern prosthetics).

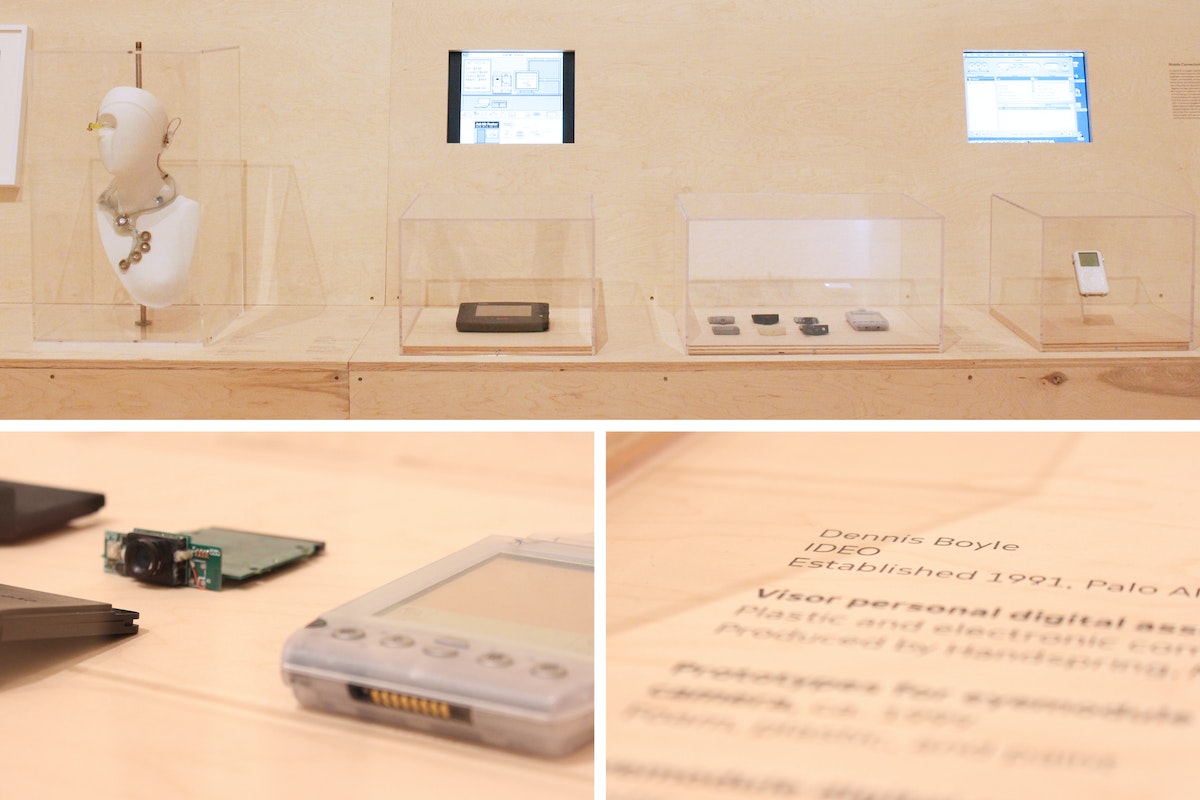

California design got swept up in the digital tsunami that WIRED was chronicling and all those "new tools" for connected living now look quaint. The first Apple desktop computer and Handspring Visor sitting under vitrines look like beige relics from a technocrypt.

IDEO’s Dennis Boyle, who led the Handspring Visor design team, told me that its eye module accessory is credited as being the first digital camera on a handheld electronic PDA. "It’s the precursor to today's cell phone cameras," he said.

I'm drunk on Kool-Aid, no doubt, but I walked away from this show marveling at how IDEO appears to be the aortic valve of California design. There are no less than five examples of our work on display: The prototype for the first Apple mouse, Thoughtless Acts? and Method Cards, the Handspring Visor, and the prototype for the Q Concept workstation, designed by David Kelley and Jim Yurchenco, Jane Fulton Suri, Dennis Boyle, and Martin Bone, respectively.

Yurchenco, who repurposed a butter dish and a roll-on deodorant ball procured at a local Palo Alto drugstore to make the earliest mouse, is struck by the crude tools designers had at their disposal back in the day:

“It was done using old techniques: a pencil and paper on a drawing board instead of 3D solid CAD to design the parts; manually machined injection molding tools and pieced together check models instead of 3D printed models. Of course, everything designed at that time was done the same way.”

Though it seemed impossible to design a mouse for less than $10 when Steve Jobs first proposed it, IDEO founder David Kelley and Yurchenco alighted upon a crucial insight:

“The most surprising thing that happened during the process was we were able to make [the mouse] low-cost by realizing it didn't have to be as precise as we first thought," Kelley says. "Because the user's human brain would intuitively move the mouse to exactly the right spot."

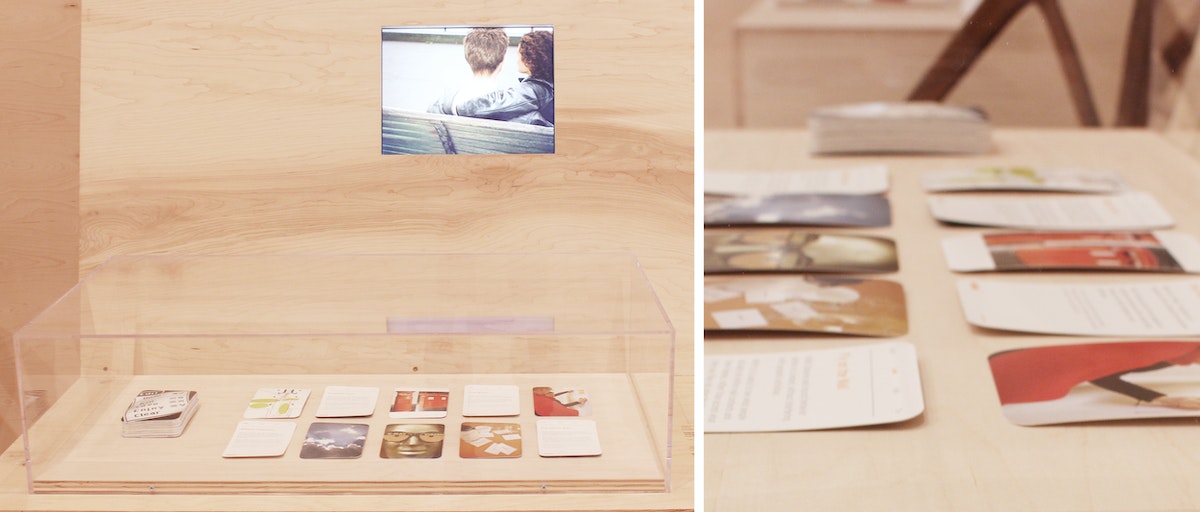

Jane Fulton Suri still expresses surprise that a simple deck of cards (Method Cards), which were published in 2003, became the foundation for IDEO's design approach:

“At the time it wasn’t obvious that sharing information about our approach and sensibilities would be a powerful way for IDEO to lead the way. It's now core to IDEO's strategy to create design tools and empower others in the world at large.”

Three of the four designers quoted above still work at IDEO. And that reminds me of another thing I love about California designers:

They never stop trying to make things better by making better things.

Next up: Nick Pajerski interviews "Designed in California" curator Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher.

Words and art

Subscribe

.svg)