Can failure be and feel productive?

Should we allow new ideas to fail?

At a recent business roundtable, the topic was how to set product innovation up for success. I spend the bulk of my days helping organizations stretch to tackle business challenges by coming up with breakthrough ideas, so it might seem sacrilegious to allow those ideas to fail. But since that breakfast, I found myself scrutinizing not only what failure looks like, but also how it feels.

There’s a saying that’s usually applied to writing: “Kill your darlings.” It’s a nudge to let go of a much-chewed-over clever phrase that doesn’t help the overall story.

We use the saying at IDEO, too. But our “darlings” are hypotheses or “sacrificial concepts” that we quickly put to the test and are willing to abandon. Iteration is the lifeblood of the design process—and the magic of it is that it allows for what Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson calls “productive failure.”

When companies face business challenges that require innovation, the instinct is to look for and land on a solution and sell it internally, so you secure permission to move forward. And what if the path you’ve chosen doesn’t pan out? We have a natural instinct to persist: The company has allocated money and resources, and it’s easier to hang onto the hope that a turnaround is just ahead than to pivot.

But hope isn’t enough in an era of new baselines like disruptive AI and climate change. Companies must stretch further, build resilience, and find ways to meet an ever-evolving new customer.

To keep pace, we have to reframe business challenges as human challenges: What is desirable from a human point of view? What do people really need? How can we help a brand like H&M meet its customers’ desire to use less plastic? And also help the retailer meet its climate goals by reducing waste from its supply chain? Insights drawn from in-depth interviews with and observation of customers and other stakeholders combined with data already collected by the organization help us generate hypotheses that we can quickly test.

In the case of H&M, we suggested replacing the plastic packaging they used to ship online orders with paper. But there were many hurdles to clear to make sure that would work across a global supply chain with multiple brands. It ended up taking several months and multiple pilots to ensure the more sustainable packaging would work.

Finding out that something doesn’t work—and, crucially, why—sets you up to more deeply understand the constraints you're operating within. And reframing an abandoned concept as a learning rather than a failure allows you to prioritize continuous improvement, keep teams motivated, and build stakeholder confidence .

Organizations may feel like they don’t have the luxury of time to test innovative ideas. But proof of concept needn’t take more than one to two weeks and can be done at low-cost. One timesaver is to test hypotheses in parallel. That approach also allows teams to let go of darling concepts and view the goal as learning rather than validation.

By one estimate, 95 percent of new products fail, and baking failure into the exploratory phase helps ensure the product or service that emerges has been battle-tested. A hypothesis that doesn’t work out isn’t a Failure, it’s a failure, and that feels different. In the case of H&M, prototyping packaging options not only led us to a paper solution that cut plastic, it led to us digging deeper on climate goals and ultimately redesigning their supply chain to cut millions of tons of waste.

At the roundtable, we talked about the challenge of working within a company culture that doesn’t tolerate failure. I’ve worked in a number of those environments and cultures; they’re tough. Failure carries emotional baggage. If you got a taste of it as a child and were a diligent but mostly average student like me, you did everything you could to avoid seeing that red letter atop a test ever again.

I’m currently working within a culture that makes room for failure. Some of that is inherent in the design process, which is optimistic and pragmatic. But my colleagues also share an important mindset. They focus more on impact than the idea or activity that produces it. There is a deep respect for diversity of perspective and a shared belief that if there’s a better way to do it, we’re going to do it that way.

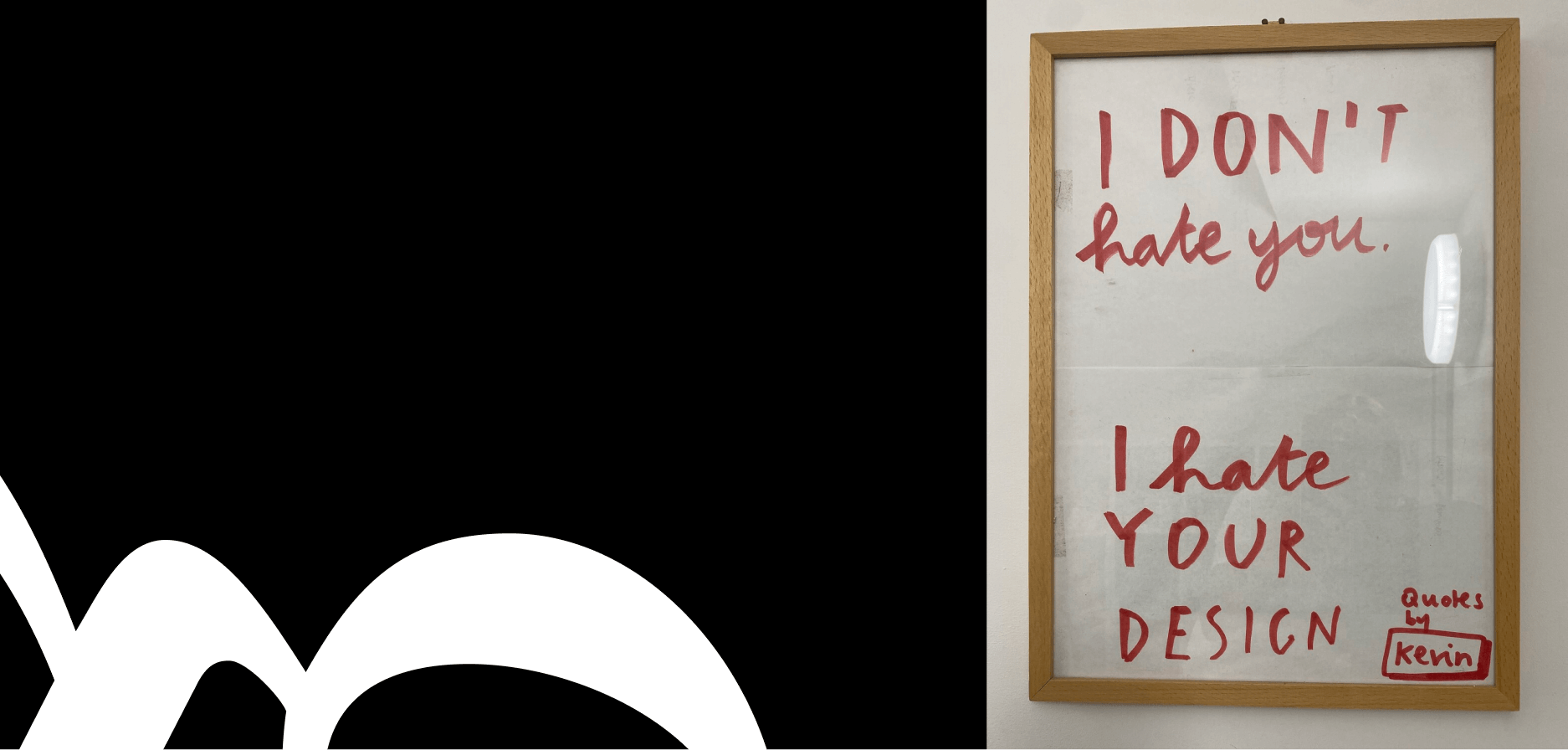

In IDEO’s London studio, we have a framed, handwritten quote: “I don’t hate you, I just hate your idea.” It was never intended to be framed, but it’s a fabulous reminder about not taking failure personally. If we truly share a collective goal of doing well and doing good, we need to generate and test as many ideas as we can—and be okay with killing our darlings to get there. It’s the only way to make real change.

Is your intolerance for failure holding you back? I’d love to hear more.

Words and art

Subscribe

.svg)