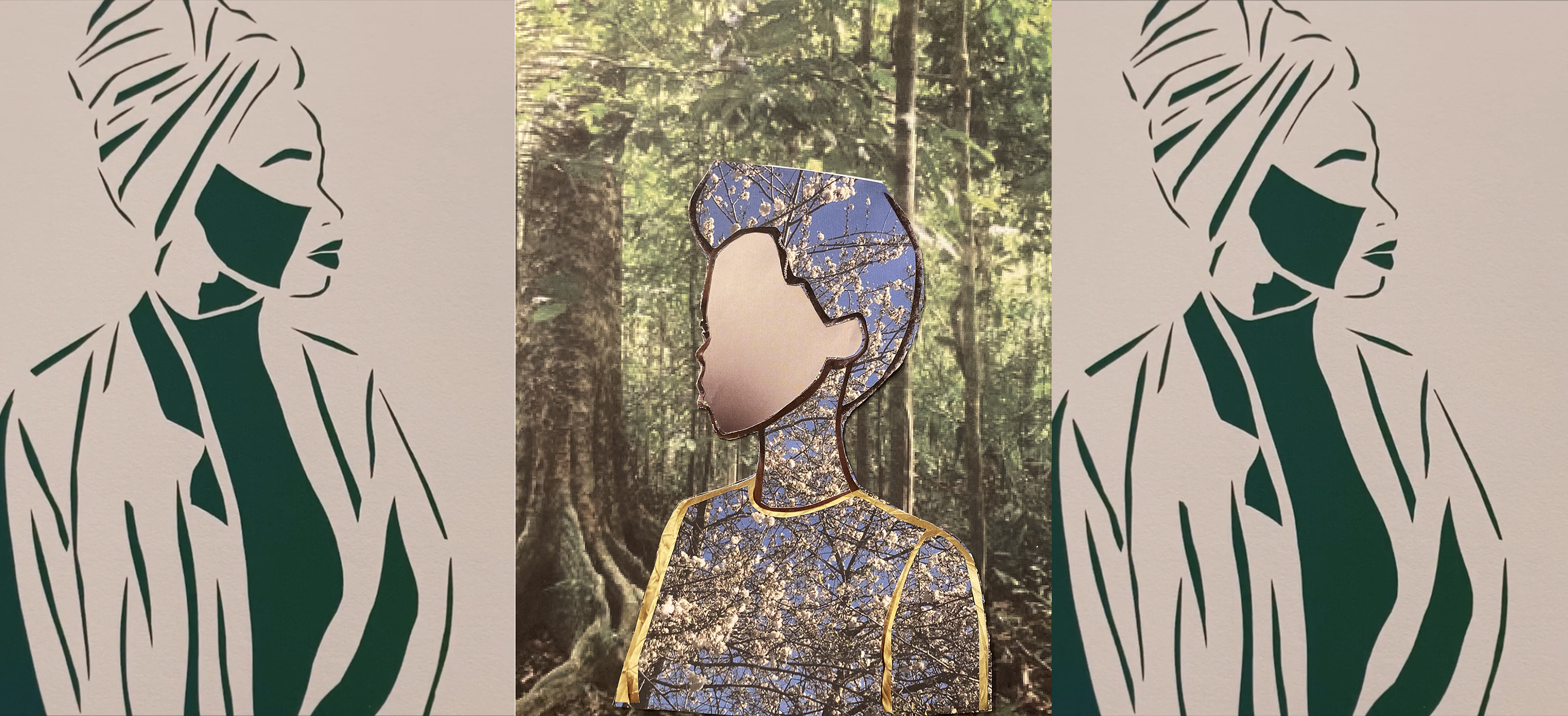

Artist George McCalman on Black history and the luxury of hope

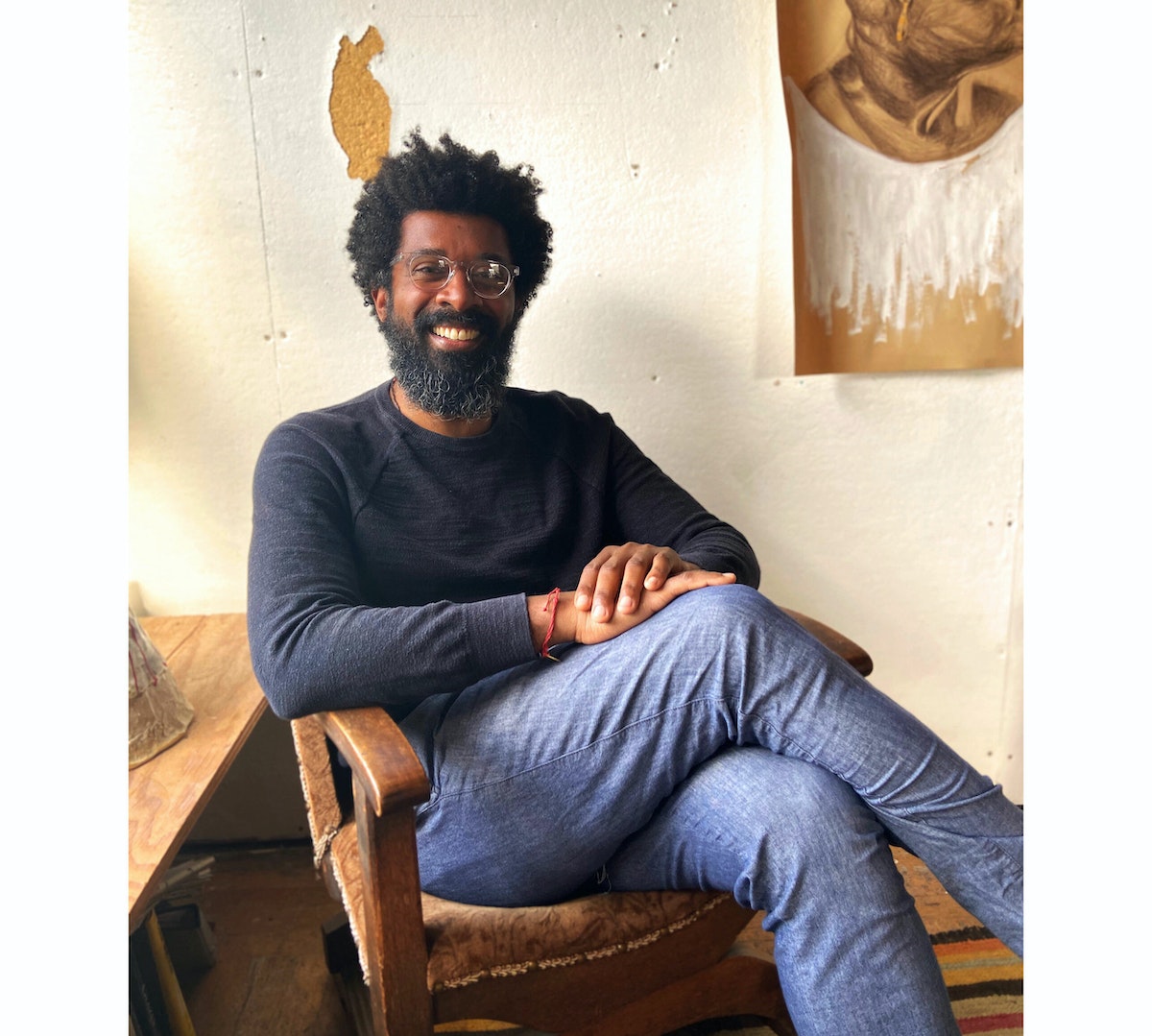

George McCalman wasn’t always a multi-hyphenate. The art director-writer-illustrator started out as a traditional graphic designer, earning his stripes through the “military training” of New York magazines in the aughts.

I met him in 2005, when he became the art director of my crafty, grassroots Berkeley magazine, ReadyMade.

In the years that followed, we laughed and wept through one of the most fruitful creative collaborations of our lives. Then, in 2011, George strapped on a jetpack, waved goodbye to publishing, and lit out to start his own eponymous juggernaut, McCalmanCo. Aside from his fertility as a creative director, illustrator, and artist, 2020 was a year of honing “Observed,” his column for the San Francisco Chronicle, into a razor-sharp instrument of cultural commentary. One of his pieces shares the backstory behind his exhibition, “Tell Me Three Things I Can Do/Return To Sender,” a collection of bold, typographic renderings of messages he received from white acquaintances in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. I caught up with George in January, 2021, to hear more about an eagerly awaited new project: Illustrated Black History: Celebrating the Iconic and the Unseen, due out from Amistad/HarperCollins in October, 2021.

In one sentence, who are you?

A polymath trying to simplify his life.

What do you do? How did you learn it?

Too many things for this format! I’m a fine artist, illustrator, art director, cultural critic, editor, writer, and professor of graphic design. I also run McCalmanCo, a design studio that does branding for companies, books, and individuals. I learned all of those things through magazine military training. I started at the peak of magazine publishing in New York and left right at the sunset in San Francisco.

One story that sums up that experience was my very last day atEntertainment Weekly. I put in an all-nighter designing the cover story on Heather Locklear at Melrose Place. I had already cleared my desk, but I needed to be there to get it done. I came in at 8 a.m. and left at 8 a.m. the next morning. I said to myself, I never want to do that again. And I never did. San Francisco offered a version of that life without ever getting to that level of insanity.

What are your 3 favorite possessions?

My home is filled with art that my friends have created. This year represents the most time I’ve spent at home, and I realized I’ve constructed my home as an altar—a totem to both friends who have passed and those who are living. So, my entire home is my favorite possession. Also, my studio. And my friendships.

What does a typical work session look like?

Communication. A lot of communication. Because every day is atypical. What is consistent in how I approach anything I do is I try to make sure I have a perspective on what I’m doing first. Whether I’m starting an illustration, painting, doing a shoot for a book, if I don’t know what I’m doing, I stop. I’ve stopped meetings, conversations, illustrations, I’m always like, Wait what am I doing, who am I talking to? It makes everything I do better.

How do you get over creative block?

If I’m having difficulty it has to do with everything outside the creative process. It’s an emotional or somatic block. When I listen to my emotions or body, all the information is there. If my body is tired, I won’t draw for a week, rather than powering through. I am prolific because I’m tuned into the lessons I’m getting from my emotional or somatic state and I don’t challenge those things. But this is not something I knew when I was younger, only in the last 10 years. I think back and my body was sending me all those signals all along.

What was the last item on your to-do list?

I’m directing a photo shoot for Bryant Terry’s new book, so I’m currently organizing a zoom call with the team. The truth is that I’m never not working—I’ve fused my personal and professional life. I learned that from James Lord and Roderick Wyllie of the landscape architect firm Surfacedesign. They are a couple who are very different people, but inseparable. They move through life with no break between work and life—they will work through a glorious dinner and while traveling—but it’s not work that’s breaking them, it’s work that’s energizing them. That joyfulness in treating their work like it’s their choice rather than their burden inspires me.

How do you see the world in 2078?

I think the U.S. will still be a messy, unsatisfying experiment. The pandemic has transformed much of this world and it will be years before we see how that’s manifested. Two words thrown around a lot are hope and optimism. That’s a very American position. I don’t really think in those terms. Do I believe we are going to make progress? Yes. But we live in a country where people don’t want the progress, so we have to figure out how to live with those who don’t think treating people of other races equally is a good idea, or that paying for the health care for everyone is a good idea, or that letting people who enter this country become citizens is a good idea. How do we reconcile these polarities? It’s not optimism or pessimism, it’s just work. My white lady friends say “I’m so hopeful now,” and I think, how wonderful for you, what a luxury that you get to be hopeful.

What's your number one bucket list item?

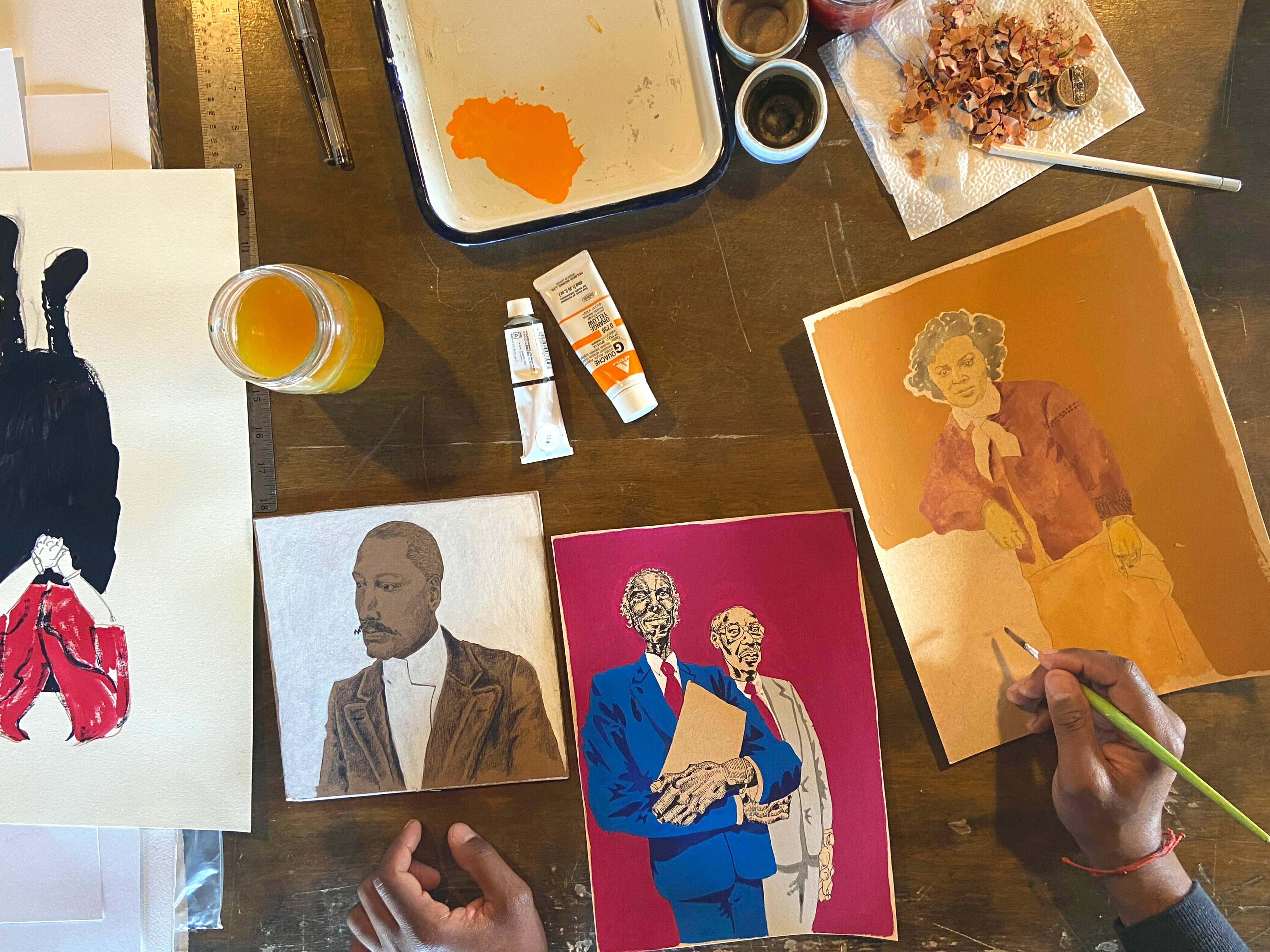

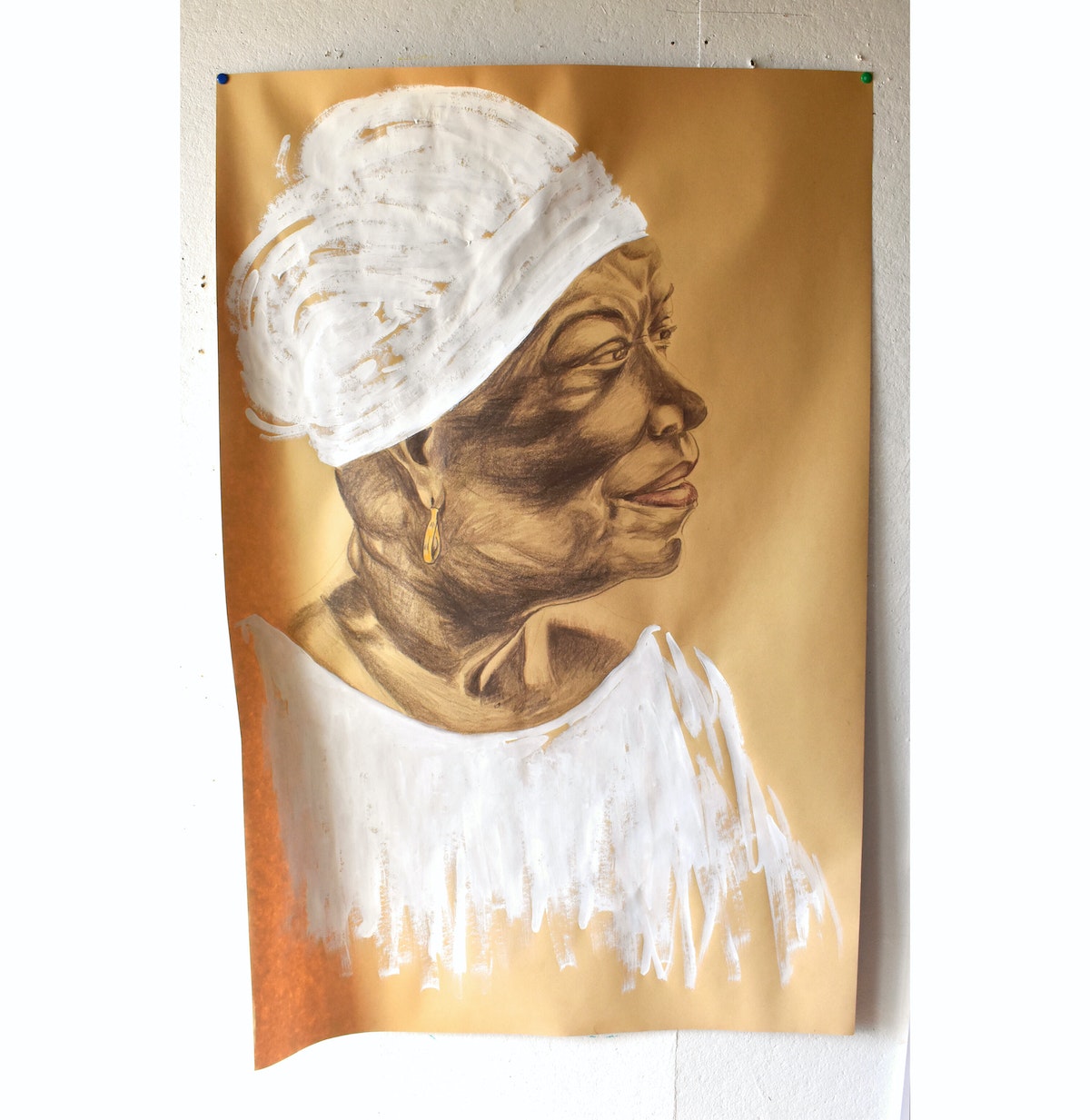

I’m doing it! To write and illustrate and design my own book. Much of Black history is reduced to 10 people, but the book I’m working on tells the story of 400 years of American history through the eyes of 150 Black pioneers. Their biographies are historical allegories in that you’ll see how the Black community, unlike the white community in this country, is very much a continuum of our ancestors passing down knowledge. It’s a contemporary telling, devoid of the dryness of historical writing. It’s celebratory of the sacrifices that some of these pioneers of business, film, art, writing and science made to enhance our ideas of democracy and justice. I’m treating them like they’re the Avengers. I hope everyone reads it. It’s a gift you can send to your slightly racist cousin, your republican father, and your apathetic aunt. I want it to be read by students and teenagers and 80-year-olds and also by those who don’t care about Black history.

Who are you creative crushin' on lately?

A short list of iconoclasts who are in their own lane:

- Bryan Stephensen of the Equal Justice Initiative

- The illustrator Lauren Tamaki

- New Yorker food writer Bryan Washington

Words and art

Subscribe

.svg)