Amp Up Your Next Sprint With These 6 Tips

Know that timeworn Henry Ford quote, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses”? Turns out Ford probably never said that. But as designers who are trying to imagine and build the future, we’ve found it to be a very useful notion.

Turns out it's really hard to get people to think about why they'd use technology they don’t understand for a problem they don’t know exists. And that's exactly the challenge we've taken on at the CoLab, IDEO’s collaborative innovation lab—to determine what humans will need in the connected future.

How does that affect our quarterly design sprints? The goal isn't faster execution—as it would be with a typical work sprint—but rather surfacing and validating new opportunities.

Here's how it works: At the start of the sprint, each multidisciplinary team (a motley crew of designers, technologists, and businesspeople who range from students to entrepreneurs to corporate representatives) is given a design brief that specifies a technology to use, like blockchain or machine learning. Teams are charged with quickly getting their heads around the emerging technology, creating their first prototype, gathering feedback, iterating, synthesizing, and sharing their design.

Over the past four years, we’ve created well over 200 prototypes and learned a ton.

Here are our best tips for how to run a highly productive design sprint:

1. Big questions need small starting points

When you’re asking a huge, provocative question, you could spend months coming up with answers. So, before the sprint, we make sure we take time to craft specific briefs to work on—design challenges that are bite-sized enough that we can (in)validate them during the course of a week, but broad enough that we can sink our teeth into them.

We might start with a question like: “How might decentralized technologies change the ways communities reduce risk?” and include a suggested prototype like: “Build a peer to peer insurance product for travel using blockchain technology.” This level of specificity can feel stifling at first—but it helps teams get moving fast toward a prototype.

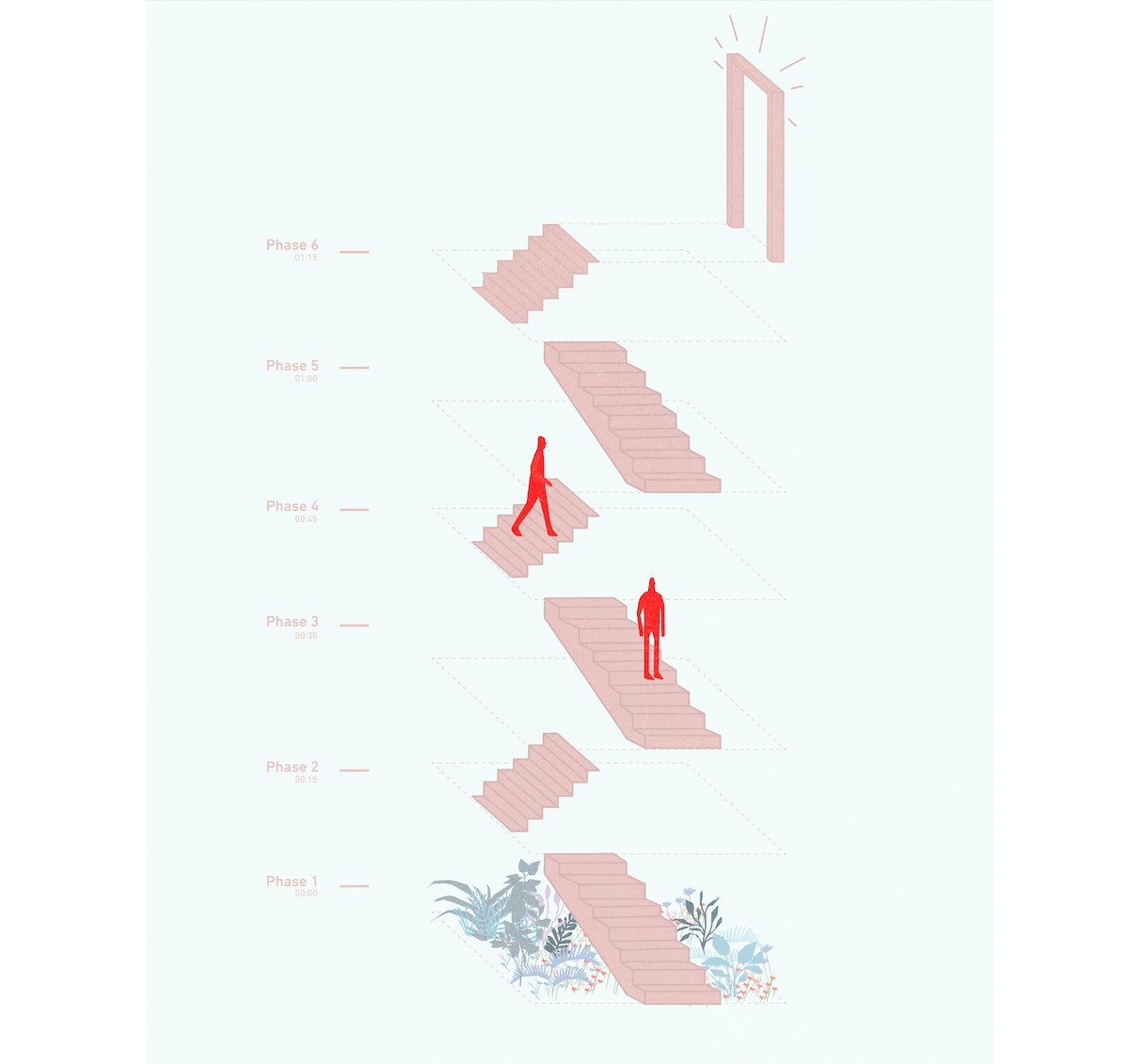

2. Timebox everything

An exploratory sprint can feel directionless at first—you’re trying to make something new with a brand new tool, which means you could do almost anything. The best way to not devolve into endless spiraling is by scheduling every phase of design down to the minute. When you know your team needs to make a decision between A and B in the next seven minutes, well, you put on your big kid pants and decide. By giving yourself a series of minideadlines, you can accomplish more iterations and ultimately, a better prototype at the end of your sprint.

3. Show up with a prototype

When you’re working with a revolutionary technology and trying to explain your idea to a potential user, their eyes glaze over. Showing up to user testing sessions with a prototype—even if it’s far from final—makes the future tangible and accessible. You’re not talking about faster horses anymore, you’ve got people imagining cars.

4. Strong ideas weakly held

Making something takes confidence, and nothing builds confidence like concrete evidence that you’re headed in the right direction. But evidence is hard to come by in the world of emerging tech. Try prototyping as if you’re right—and then listening as if you’re wrong. This means putting your prototype in front of people and learning from all the ways it didn’t work for them—giving you both evidence and direction on what to build.

5. Find the right questions, not perfect solutions

Exploration is about charting unfamiliar territory. Sometimes that means you get it all wrong and end up at a dead-end. But that doesn’t mean the sprint was a failure! As we said, the goal of an exploratory sprint is not to execute a million dollar idea in record time, but to surface new opportunities.

At the end of the sprint, when it’s time to present your prototype, focus the conversation on what you learned: What would you build next time to make an even better, more human-centered solution? What advice would you give to others designing with these technologies?

6. Science fair, not pitch deck

Rather than jazz hands, Powerpoints, and promises of what your prototype could do, we always end our sprints in a science fair format: multiple hands-on demos happening alongside one another, with lots of room for discussion.

This lets people experience prototypes individually and then come back together to reflect on how the ideas worked for them (or didn’t). It’s another round of user feedback that furthers our learning and participants walk away with real insights that might apply to their work beyond the sprint.

It’s not always easy to run a sprint. It means breaking out of your regular work routine and collaborating with a team to do something intense and exhausting that you aren’t always sure is going to work. It means building with tools you don’t know how to use (yet).

But when we follow these rules, our sprints offer up reams of new ideas, insights, opportunities, and next steps that send us galloping toward a more human-centered future.

Words and art

Subscribe

.svg)